There has been much speculation as to the motives of Adam Lanza, the shooter at Sandy Hook Elementary. More to the point, there has been much speculation about his mental health.

It is only natural for us to suppose that anyone who would do a thing like this must be psychologically or emotionally troubled — that is, exceptionally and diagnostically so.

In a recent interview with WGRZ (www.wgrz.com), University of Buffalo Department of Psychiatry Chair Steven L. Dubovsky, MD, stated that many perpetrators of these types of crimes do not have any psychiatric illnesses. Rather, they tend to be “losers” and “cowards” who seek fame and notoriety and think that this is the only way they will be able to achieve it.

My reference to Dubovsky is introductory in nature. It is not my intention in this post to argue that Adam Lanza did not have a psychiatric illness of some sort. For all I know, he very well may or may not have. But I do think we need to be careful about quickly jumping to the conclusion that anyone who commits a horrible crime such as this must necessarily be mentally ill.

Why do I say that? Well, one word — scapegoating.

There are many kinds of mental illness. All of them present great challenges to the people who have them, and the stigma that society has historically attached to them doesn’t help.

Nor is societal stigma limited to mental illnesses. To some extent, it still embraces any kind of documentable mental difference. I work with people with mental retardation and developmental disabilities, and I have directly and indirectly encountered some of the misconceptions and impatience that are still out there. After the recent tragedy and the quick search for a psychiatric “label” for the killer, I am afraid of how the stigma might yet grow.

Don’t get me wrong — the question of whether or not someone like Lanza has a diagnosable problem should be explored. And to be sure, there are certain types of mental illness that make people more prone to committing violent acts, and the appropriate safeguards should be in place to make sure these people don’t harm themselves or others.

What concerns me is the simple assertion that I have heard people make in conversation: “This young man must have had something wrong with him (that is, psychiatrically).”

If we convince ourselves that only those who are exceptionally troubled have the capacity to commit horrible acts like the one at Sandy Hook, we do not automatically condemn all such people; but I think we do make a couple of mistakes:

1) We “acquit” ourselves and encourage a sort of complacent self-righteousness; and

2) By saying that brutal acts of carnage and violence are exclusive to those who are mentally “other,” we implicitly amplify the stigma attached to this “otherness.”

For me, as a Catholic, the tragedy at Sandy Hook brings home a reality confirmed by one of the Church’s most controversial doctrines: Original Sin.

Even if Lanza was mentally ill, Dubovsky’s words give us pause. We have to face an unpleasant fact: There is evil in the human heart. That does not mean that human beings are evil, per se. On the contrary, my Catholic Faith tells me that all people are created in God’s image and are therefore essentially good.

However, the divine image in each of us is tarnished, and we all have a tendency towards things that we know are not right.

And you don’t have to be a Catholic to believe this. I attended a seminar a little over two years ago that was conducted by Barry Gan, PhD, director of the Center for Nonviolence at St. Bonaventure University. Gan is Jewish, and he talked about nonviolence from a non-denominational and very much secular perspective. One of the things Gan stressed in one of his talks was that each and every one of us is capable of both great good and great evil (as an example of this paradox, he cited Osama bin Laden, who became something of a legend in Afghanistan for his great philanthropic work and kindness to children in hospitals long before the September 11th attacks).

But most of us would rather not face the darkness and guilt in our own hearts. For most of us, it is too much. So what we tend to do — even if subconsciously — is select a certain group of people, set them apart, and pile all of our guilt onto them. We will stigmatize a certain “class” of individuals as being particularly bad, dangerous, or unwelcome (or even unredeemable sometimes) so that we can compare ourselves favorably against them.

Let’s face it: Most of us will not go out and kill people, and thank God for that. And I’m not saying that we should be over-scrupulous about every little flaw we find in ourselves, as if an explosion of violence or other similar extremes are inevitable. But big sins tend to have small beginnings, and we all experience those beginnings.

Furthermore, as my faith proclaims, each and every human being’s personal sins contribute, often in mysterious ways, to the overall moral disorder of the world. So if we want to see things change, we must begin with ourselves…with our own hearts.

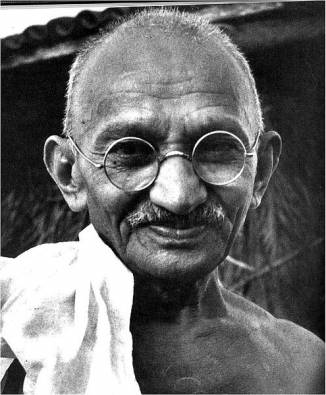

As Gandhi famously said, we must “be the change (we) wish to see in the world.”

While the doctrine of Original Sin seems, at the outset, bleak and anti-human, in conjunction with Christ’s redemptive death, resurrection, ascension into Heaven, and gift of the Holy Spirit it is ultimately a life-giving reality. I see two reasons for this:

1) It gives us a degree of control in the midst of chaos. While we cannot always control what other people do, we can choose, with the help of God’s grace, to grow in virtue ourselves. By becoming better and more virtuous people, we become channels through which that divine grace that can renew the world may enter the world.

2) It stops us from looking down on others and inspires us to look up on their behalf. When we look at those we might consider especially bad and consider that both they and we are capable both of great evil and great good, we realize — and may then act out of the realization — that no one is beyond hope.

That said, let me conclude by summarizing my initial point. Yes, we should look at psychological issues that may have affected Adam Lanza’s actions. But we also have to remember that the mentally ill and mentally “different” do not have a monopoly on evil or dangerous acts. Nor, for that matter, should we encourage the idea that these kinds of differences necessarily imply dangerousness.

Now is not the time to encourage scapegoating or stereotypes. Rather, it is a time to realize that each of us is called to be a light in the midst of this present darkness.

Images obtained through a Google image search.